Manarah is an old Arabic word for ‘lighthouse’, a place of light to help those on a voyage find their way. Later the word developed into ‚minaret‘ – which is the tower of a mosque. I found out about this a few years ago whilst doing research on this topic. The Swiss populace had just voted not to allow the building of minarets in their country.

I like the image. A lighthouse gives guidance and orientation but it does not take you by the hand. The symbol of the lighthouse does not make it too easy for you. You’ve still got to do the travelling by yourself. You’re still responsible. You are free to make your own choices.

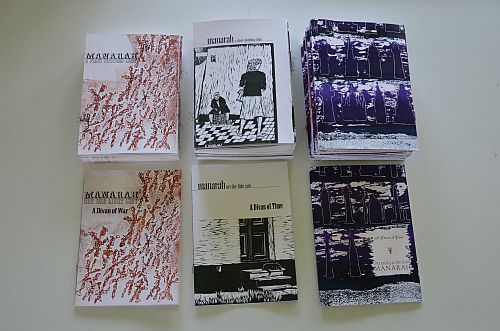

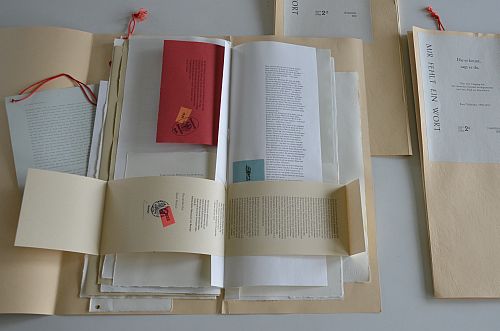

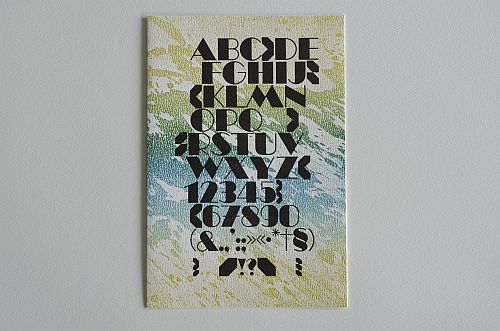

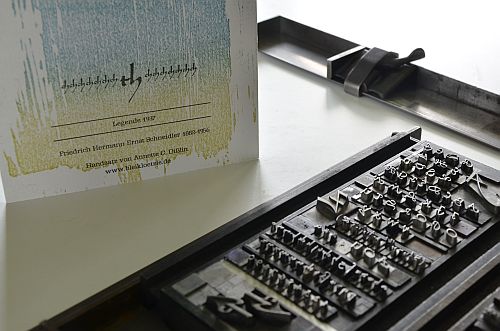

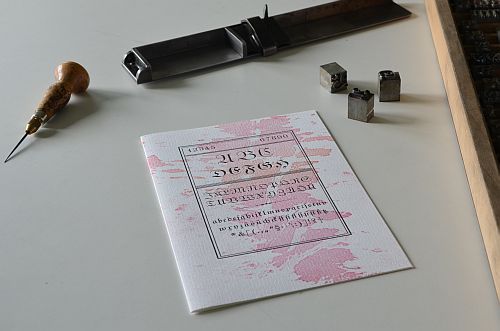

My ‚Manarah‘ is a book-arts magazine printed letterpress using metal type. The first 3 issues were published in 2011. Every issue is a ‚Divan‘, a collection of poetry on a chosen subject. ‚Divan‘ is a Persian word for the collection of poems. I had decided that these first 3 issues would be my contribution to the al-Mutanabbi Street inventory project. This project is one response to the bombing of al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad back in March 2009. During the attack the centuries old city district of bookselling as well as literary and intellectual life was totally destroyed. One hundred and thirty lives were lost or injured. An ancient city’s cultural heritage was left shattered. Beau Beausoleil, a Californian writer and bookseller with his al-Mutanabbi Street coalition, has put out the global call to follow the „al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here“ campaign.

They asked bookartists all over the world to follow their call and built up a new inventory of books for al-Mutanabbi Street by making 3 works of bookart each.

The 3 themes I choose for my three issues were: war, time and love. I felt it would need love and take time to overcome the destruction and suffering caused by war.

From the time when I realized that there was something the adults called ‚News‘, this News was usually about war and death. During my childhood and teenage years there were wars and conflicts in Belfast, Lebanon and the Near East and in the Basque country of northwest Spain. Of course there were other wars and conflicts elsewhere, but these were the theatres of war I remember during my formative years. Some of these wars went on for decades; many of them are still no closer to a peaceful resolution. Thousands of children, born in these places, die during a bombing raid or get caught in sniper fire. If they survive they lead a life of permanent threat, danger and hatred. They could lose any of their family or friends at any moment. It becomes almost impossible to lead a normal life, have a proper education, earn a decent wage, build up a career, raise a family or even build a small house. How can one lead a normal life, when everything can be taken away from you at any moment?

I feel the deepest respect for any person who grew up during a war or a regional conflict and who will stand up for peace. Someone, who will still make every effort to stand strongly against hatred and against the lies and distortions of the truth of war; someone who is convinced that war will never give an answer nor be a solution – and who has the courage to say so.

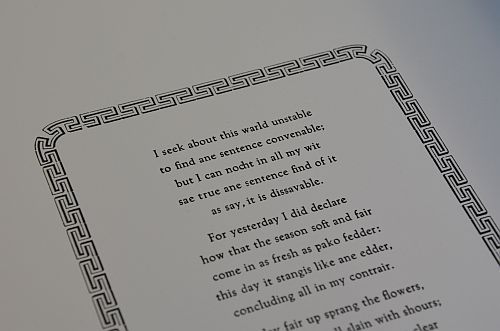

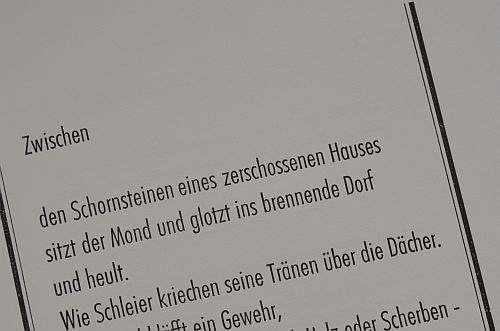

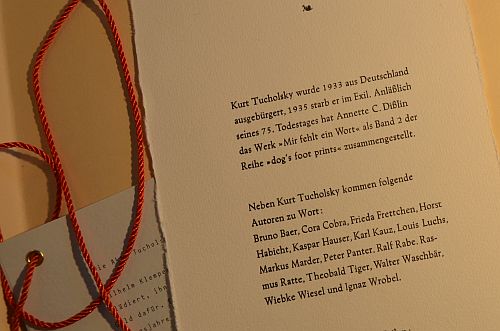

The choice of poems in all my Manarah issues covers a period of four centuries going back to the 16th century with William Dunbar being the eldest of the chosen writers. I also feature a number of poets who died during WWI.

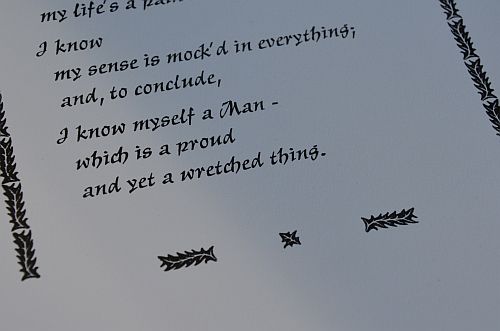

These poems tell of despair and hope, of pain and solace. They raise questions and seek answers that have been troubling mankind ever since he gained self-awareness. The collection of poems tells of the deeply felt longing for a life lived in peace and within a community full of loving understanding. They express the wish for tolerance and the possibility for one and all, to gain a state of inner contentment and happiness. These have been the treasures of mankind – and so they should remain for all times. Poems have been chosen from English and German sources and they have been printed all in their original wording with no translations provided.

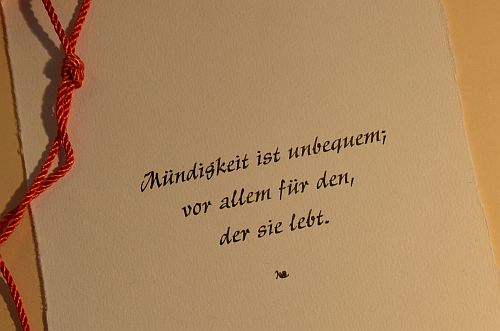

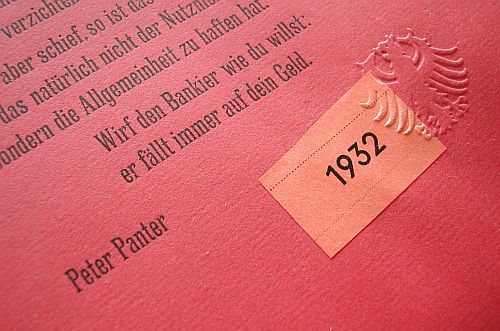

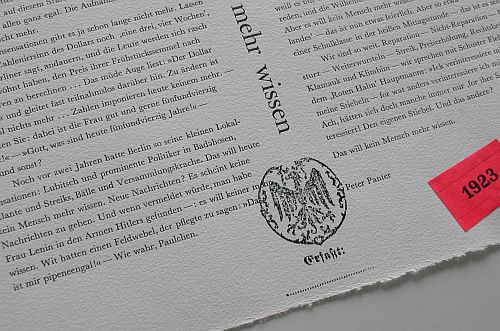

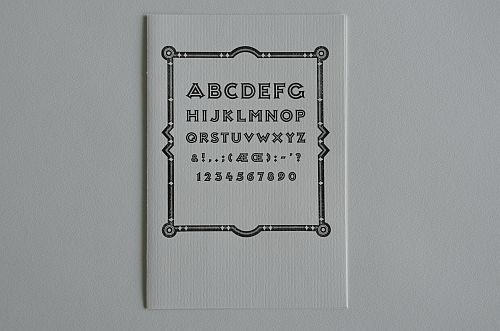

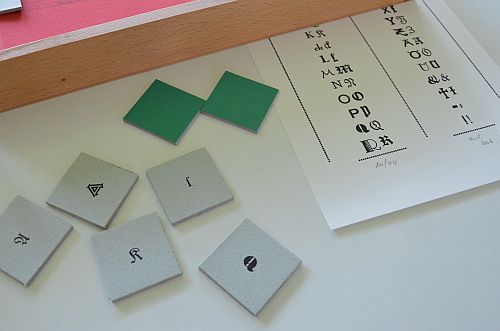

Covers are either woodcuts or linoprints. All poems have been set by hand from individually chosen metal type and ornaments. Every issue is a limited edition, numbered and signed, with less than 25 copies each. The issue on War has ten poems, the issue on Time has nine and the issue on Love has thirteen poems. This edition on Love also comes with a linoprint portrait of Joseph von Eichendorff, one of the poets. Copies are hand sewn with black or red thread.

To view this work, please visit: http://www.bleikloetzle-goes-british.de/html/manarah.html